The Only Measure of Center That Can Be Found for Both Quantitative and Qualitative Data Is the

- Research commodity

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Using quantitative and qualitative information in wellness services enquiry – what happens when mixed method findings disharmonize? [ISRCTN61522618]

BMC Health Services Research volume 6, Article number:28 (2006) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

In this methodological paper we document the estimation of a mixed methods written report and outline an arroyo to dealing with apparent discrepancies between qualitative and quantitative research data in a airplane pilot written report evaluating whether welfare rights advice has an impact on health and social outcomes among a population aged 60 and over.

Methods

Quantitative and qualitative information were collected contemporaneously. Quantitative data were collected from 126 men and women aged over 60 within a randomised controlled trial. Participants received a total welfare benefits cess which successfully identified additional financial and not-financial resource for sixty% of them. A range of demographic, health and social outcome measures were assessed at baseline, six, 12 and 24 calendar month follow up. Qualitative data were collected from a sub-sample of 25 participants purposively selected to take function in individual interviews to examine the perceived affect of welfare rights advice.

Results

Carve up assay of the quantitative and qualitative data revealed discrepant findings. The quantitative data showed petty evidence of significant differences of a size that would be of practical or clinical interest, suggesting that the intervention had no touch on these result measures. The qualitative information suggested wide-ranging impacts, indicating that the intervention had a positive effect. Half dozen means of farther exploring these information were considered: (i) treating the methods as fundamentally unlike; (ii) exploring the methodological rigour of each component; (3) exploring dataset comparability; (four) collecting further information and making further comparisons; (v) exploring the process of the intervention; and (vi) exploring whether the outcomes of the two components lucifer.

Conclusion

The written report demonstrates how using mixed methods can lead to different and sometimes alien accounts and, using this six step arroyo, how such discrepancies tin can be harnessed to interrogate each dataset more than fully. Not only does this raise the robustness of the written report, it may atomic number 82 to unlike conclusions from those that would have been drawn through relying on one method alone and demonstrates the value of collecting both types of data within a single written report. More widespread utilize of mixed methods in trials of complex interventions is probable to raise the overall quality of the evidence base.

Groundwork

Combining quantitative and qualitative methods in a single study is not uncommon in social research, although, 'traditionally a gulf is seen to exist betwixt qualitative and quantitative research with each belonging to distinctively different paradigms'. [ane] Inside health inquiry there has, more recently, been an upsurge of involvement in the combined use of qualitative and quantitative methods, sometimes termed mixed methods research [2] although the terminology can vary. [3] Greater interest in qualitative inquiry has come about for a number of reasons: the numerous contributions fabricated past qualitative inquiry to the study of health and illness [iv–vi]; increased methodological rigor [7] within the qualitative image, which has made it more acceptable to researchers or practitioners trained inside a predominantly quantitative prototype [8]; and, because combining quantitative and qualitative methods may generate deeper insights than either method alone. [9] It is now widely recognised that public health problems are embedded inside a range of social, political and economic contexts. [10] Consequently, a range of epidemiological and social scientific discipline methods are employed to enquiry these circuitous bug. [eleven] Further legitimacy for the use of qualitative methods alongside quantitative has resulted from the recognition that qualitative methods can make an important contribution to randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating complex wellness service interventions. There is published work on the various ways that qualitative methods are beingness used in RCTs (east.g. [12, 13] but piffling on how they can optimally enhance the usefulness and policy relevance of trial findings. [xiv, 15]

A number of mixed methods publications outline the various ways in which qualitative and quantitative methods can be combined. [1, 2, 9, sixteen] For the purposes of this paper with its focus on mixed methods in the context of a pilot RCT, the significant aspects of mixed methods appear to be: purpose, procedure and, analysis and interpretation. In terms of purpose, qualitative enquiry may exist used to aid identify the relevant variables for report [17], develop an musical instrument for quantitative enquiry [18], to examine dissimilar questions (such as acceptability of the intervention, rather than its outcome) [19]; and to examine the same question with dissimilar methods (using, for case participant observation or in depth interviews [1]). Process includes the priority accorded to each method and ordering of both methods which may be concurrent, sequential or iterative. [20] Bryman [nine] points out that, 'nearly researchers rely primarily on a method associated with either quantitative or qualitative methods and and then buttress their findings with a method associated with the other tradition' (p128). Both datasets may be brought together at the 'analysis/estimation' stage, often known equally 'triangulation' [21]. Brannen [i] suggests that most researchers have taken this to mean more than one blazon of data, but she stresses that Denzin's original conceptualisation involved methods, data, investigators or theories. Bringing different methods together almost inevitably raises discrepancies in findings and their interpretation. Nevertheless, the investigation of such differences may be every bit illuminating as their points of similarity. [i, 9]

Although mixed methods are now widespread in wellness research, quantitative and qualitative methods and results are often published separately. [22, 23] It is relatively rare to see an account of the methodological implications of the strategy and the way in which both methods are combined when interpreting the data within a detail report. [1] A notable exception is a study showing difference between qualitative and quantitative findings of cancer patients' quality of life using a detailed case study approach to the information. [xiii]

By presenting quantitative and qualitative data nerveless within a airplane pilot RCT together, this newspaper has iii chief aims: firstly, to demonstrate how divergent quantitative and qualitative information led usa to interrogate each dataset more fully and assisted in the interpretation procedure, producing a greater research yield from each dataset; secondly, to demonstrate how combining both types of data at the analysis phase produces 'more than the sum of its parts'; and thirdly, to emphasise the complementary nature of qualitative and quantitative methods in RCTs of complex interventions. In doing so, we demonstrate how the combination of quantitative and qualitative data led united states to conclusions different from those that would have been drawn through relying on one or other method lone.

The written report that forms the footing of this paper, a pilot RCT to examine the impact of welfare rights advice in principal care, was funded under the UK Department of Health's Policy Research Program on tackling health inequalities, and focused on older people. To engagement, little research has been able to demonstrate how wellness inequalities can exist tackled by interventions within and exterior the health sector. Although living standards take risen amidst older people, a mutual feel of growing old is worsening material circumstances. [24] In 2000–01 there were 2.3 1000000 Great britain pensioners living in households with below lx per cent of median household income, after housing costs. [25] Older people in the UK may be eligible for a number of income- or inability-related benefits (the latter could be non-financial such as parking permits or adaptations to the home), but it has been estimated that approximately i in four (about one million) U.k. pensioner households do not claim the support to which they are entitled. [26] Activity to facilitate access to and uptake of welfare benefits has taken place outside the Uk wellness sector for many years and, more recently, has been introduced inside parts of the health service, but its potential to benefit health has non been rigorously evaluated. [27–29]

Methods

There are a number of models of mixed methods inquiry. [2, 16, xxx] We adopted a model which relies of the principle of complementarity, using the strengths of one method to heighten the other. [30] We explicitly recognised that each method was appropriate for dissimilar enquiry questions. We undertook a pragmatic RCT which aimed to evaluate the health effects of welfare rights communication in master care amidst people aged over lx. Quantitative information included standardised event measures of health and well-being, wellness related behaviour, psycho-social interaction and socio-economic status ; qualitative data used semi-structured interviews to explore participants' views about the intervention, its outcome, and the acceptability of the inquiry process.

Following an before qualitative airplane pilot study to inform the selection of advisable consequence measures [31], contemporaneous quantitative and qualitative data were nerveless. Both datasets were analysed separately and neither compared until both analyses were complete. The sampling strategy mirrored the embedded design; probability sampling for the quantitative study and theoretical sampling for the qualitative study, done on the basis of factors identified in the quantitative study.

Approving for the written report was obtained from Newcastle and North Tyneside Joint Local Research Ethics Committee and from Newcastle Primary Care Trust.

The intervention

The intervention was delivered by a welfare rights officer from Newcastle Urban center Council Welfare Rights Service in participants' own homes and comprised a structured assessment of current welfare status and benefits entitlement, together with active assistance in making claims where appropriate over the following half dozen months, together with necessary follow-upward for unresolved claims.

Quantitative study

The design presented upstanding dilemmas as it was felt problematic to deprive the control group of welfare rights advice, since in that location is acceptable show to show that information technology leads to significant financial gains. [32] To circumvent this dilemma, nosotros delivered welfare rights advice to the control group 6 months later on the intervention grouping. A single-blinded RCT with allocation of individuals to intervention (receipt of welfare rights consultation immediately) and command status (welfare rights consultation half-dozen months after entry into the trial) was undertaken.

4 general practices located at five surgeries across Newcastle upon Tyne took function. Three of the practices were located in the meridian x per cent of well-nigh deprived wards in England using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (2 in the tiptop one percent – ranked 30th and 36th almost deprived); the other practice was ranked three,774 out of a full of 8,414 in England. [33]

Using practise databases, a random sample of 100 patients aged sixty years or over from each of four participating practices was invited to accept part in the report. Only one individual per household was allowed to participate in the trial, but if a partner or other adult household member was also eligible for benefits, they also received welfare rights advice. Patients were excluded if they were permanently hospitalised or living in residential or nursing care homes.

Written informed consent was obtained at the baseline interview. Structured face up to face interviews were carried out at baseline, six, 12 and 24 months using standard scales covering the areas of demographics, mental and physical health (SF36) [34], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [35], psychosocial descriptors (e.g. Social Back up Questionnaire [36] and the Self-Esteem Inventory, [37], and socioeconomic indicators (e.g. affordability and financial vulnerability). [38] Additionally, a short semi-structured interview was undertaken at 24 months to ascertain the perceived affect of additional resources for those who received them.

All wellness and welfare assessment data were entered onto customised MS Access databases and checked for quality and completeness. Data were transferred to the Statistical Parcel for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v11.0 [39] and STATA v8.0 for analysis. [40]

Qualitative study

The qualitative findings presented in this paper focus on the impact of the intervention. The sampling frame was formed by those (n = 96) who gave their consent to be contacted during their baseline interview for the RCT. The study sample comprised respondents from intervention and command groups purposively selected to include those eligible for the following resources: financial only; non-financial only; both financial and non fiscal; and, none. Sampling continued until no new themes emerged from the interviews; until data 'saturation' was reached. [21]

Initial interviews took identify between Apr and December 2003 in participants' homes afterwards their welfare rights cess; follow-up interviews were undertaken in January and Feb 2005. The semi-structured interview schedule covered perceptions of: touch of fabric and/or financial benefits; impact on mental and/or concrete wellness; bear upon on health related behaviours; social benefits; and views about the link between material resources and health. All participants agreed to the interview being sound-recorded. Immediately afterwards, observational field notes were made. Interviews were transcribed in full.

Data assay largely followed the framework approach. [41] Data were coded, indexed and charted systematically; and resulting typologies discussed with other members of the enquiry team, 'a pragmatic version of double coding'. [42] Constant comparing [43] and deviant case assay [44] were used since both methods are important for internal validation. [seven, 42] Finally, sets of categories at a higher level of abstraction were developed.

A brief semi-structured interview was undertaken (by JM) with all participants who received additional resources. These interview information explored the bear upon data of additional resources on all of those who received them, not just the qualitative sub-sample. The data were independently coded by JM and SM using the same coding frame. Discrepant codes were examined by both researchers and a final code agreed.

Results

Quantitative report

One hundred and twenty vi people were recruited into the study; there were 117 at 12 month follow-up and 109 at 24 months (five deaths, one moved, the remainder declined).

Tabular array 1 shows the distribution of financial and not-financial benefits awarded every bit a result of the welfare assessments. Sixty percent of participants were awarded some class of welfare benefit, and just over forty% received a financial benefit. Some households received more than one type of benefit.

Table 2 compares the quantitative and qualitative sub-samples on a number of personal, economic, wellness and lifestyle factors at baseline. Intervention and control groups were comparable.

Tabular array three compares consequence measures by award group, i.e. no award, non-financial and financial and shows only pocket-size differences between the hateful changes across each group, none of which were statistically meaning. Other analyses of the quantitative information compared the changes seen between baseline and half dozen months (by which fourth dimension the intervention group had received the welfare rights communication but the command group had not) and found little evidence of differences between the intervention and command groups of any practical importance. The only statistically significant deviation between the groups was a pocket-sized decrease in financial vulnerability in the intervention group after 6 months. [45]

In that location was petty bear witness for differences in health and social outcomes measures every bit a event of the receipt of welfare advice of a size that would be of major applied or clinical involvement. All the same, this was a pilot report, with just the power to notice large differences if they were present. One reason for a lack of difference may exist that the scales were less appropriate for older people and did not capture all relevant outcomes. Another reason for the lack of differences may be that insufficient numbers of people had received their benefits for long enough to allow any health outcomes to have changed when comparisons were made. Xiv per cent of participants constitute to be eligible for financial benefits had not started receiving their benefits by the fourth dimension of the first follow-up interview after their benefit cess (six months for intervention, 12 months for control); and those who had, had just received them for an average of 2 months. This is likely to take diluted whatsoever touch on of the intervention outcome, and might account, to some extent, for the lack of observed effect.

Qualitative study

Xx 5 interviews were completed, fourteen of whom were from the intervention group. 10 participants were interviewed with partners who made active contributions. Twenty two follow-up interviews were undertaken between twelve and xviii months later (iii individuals were too ill to have part).

Table 1 (5th column) shows that xiv of the participants in the qualitative study received some fiscal award. The median income gain was (€84, $101) (range £10 (€15, $18) -£100 (€148, $178)) representing a 4%-55% increase in weekly income. xviii participants were in receipt of do good, either as a effect of the electric current intervention or because of claims fabricated prior to this study.

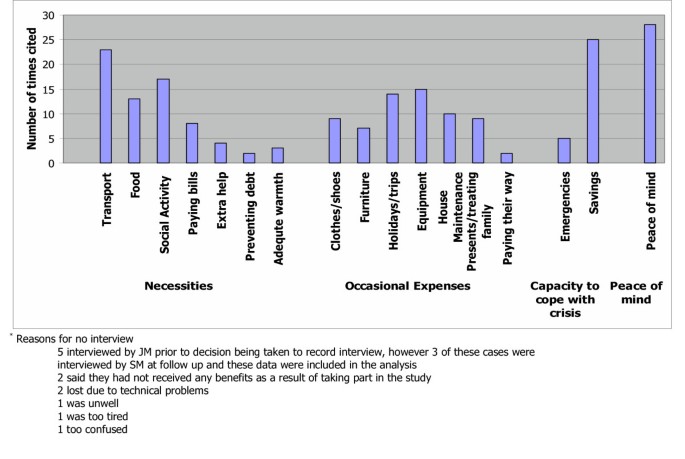

By the follow-upward (FU) interviews all but one participant had been receiving their benefits for between 17 and 31 months. The intervention was viewed positively by all interviewees irrespective of outcome. However, for the fourteen participants who received additional fiscal resources the impact was considerable and accounts revealed a broad range of uses for the actress money. Participants' accounts revealed iv linked categories, summarised on Table iv. Firstly, increased affordability of necessities, without which maintaining independence and participating in daily life was difficult. This included accessing ship, maintaining social networks and social activities, buying better quality nutrient, stocking up on food, paying bills, preventing debt and affording paid help for household activities. Secondly, occasional expenses such equally clothes, household equipment, piece of furniture and holidays were more affordable. Thirdly, extra income was used to act as a cushion against potential emergencies and to increment savings. Fourthly, all participants described the easing of financial worries every bit bringing 'peace of mind'.

Without exception, participants were of the view that extra money or resource would not improve existing wellness problems. The reasons backside these strongly held views about individual health conditions was by and large that their poor health was attributed to specific wellness atmospheric condition and a combination of family unit history or fate, which were immune to the effects of money. About participants had more than 1 chronic status and felt that because of these conditions, plus their historic period, boosted coin would have no result.

All the same, a number of participants linked the impact of the intervention with improved ways of coping with their conditions considering of what the extra resources enabled them to do:

Mrs T: Having money is not going to improve his health, nosotros could win the lottery and he would still have his health problems.

Mr T: No, only we don't demand to worry if I wanted .... Well I hateful I eat a lot of love and I think it's very good, very healthful for you ... at one time we couldn't have afforded to buy these things. Now we can go and buy them if I fancy something, but go and go it where we couldn't before.

Mrs T: Although the Omnipresence Allowance is actually his [partners], it'due south fabricated me relax a bit more ...I definitely worry less now (N15, female, 62 and partner)

Despite the fact that no-ane expected their ain wellness conditions to amend, well-nigh people believed that there was a link betwixt resources and wellness in a more abstract sense, either considering they experienced problems affording necessities such as salubrious food or maintaining adequate oestrus in their homes, or because they empathised with those who lacked money. Participants linked adequate resource to maintaining health and contributing to a sense of well-beingness.

Money does have a lot to do with health if you are poor. Information technology would take a lot to practice with your health ... I don't buy loads and loads of luxuries, only I know I tin become out and get the nutrient we demand and that sort of matter. I remember that money is a big role of how a business firm, or how people in that firm are. (N13, female, 72)

Comparison the results from the two datasets

When the separate analyses of the quantitative and qualitative datasets after the 12 month follow-upwardly structured interviews were completed, the discrepancy in the findings became apparent. The quantitative study showed little prove of a size that would be of applied or clinical interest, suggesting that the intervention had no impact on these outcome measures. The qualitative written report institute a wide-ranging impact, indicating that the intervention had a positive event. The presence of such inter-method discrepancy led to a not bad deal of discussion and fence, equally a result of which we devised 6 ways of further exploring these data.

(i) Treating the methods equally fundamentally different

This process of simultaneous qualitative and quantitative dataset interrogation enables a deeper level of analysis and interpretation than would exist possible with one or other alone and demonstrates how mixed methods inquiry produces more than the sum of its parts. It is worth emphasising still, that information technology is not wholly surprising that each method comes upwardly with divergent findings since each asked different, but related questions, and both are based on fundamentally different theoretical paradigms. Brannen [1] and Bryman [ix] debate that it is essential to take account of these theoretical differences and caution against taking a purely technical arroyo to the use of mixed methods, a simple 'bolting together' of techniques. [17] Combining the two methods for crossvalidation (triangulation) purposes is not a feasible option because it rests on the premise that both methods are examining the same inquiry problem. [1] We take approached the divergent findings as indicative of different aspects of the phenomena in question and searched for reasons which might explain these inconsistencies. In the approach that follows, we take treated the datasets every bit complementary, rather than attempt to integrate them, since each approach reflects a different view on how social reality ought to be studied.

(two) Exploring the methodological rigour of each component

Information technology is standard exercise at the data analysis and interpretation phases of any study to scrutinise methodological rigour. However, in this example, nosotros had another dataset to use as a yardstick for comparison and it became clear that our interrogation of each dataset was informed to some extent past the findings of the other. Information technology was not the instance that we expected to obtain the same results, but conspicuously the divergence of our findings was of swell interest and fabricated us more circumspect about each dataset. Nosotros began past examining possible reasons why at that place might be bug with each dataset individually, but found ourselves continually referring to the results of the other study every bit a benchmark for comparison.

With regard to the quantitative study, it was a airplane pilot, of small-scale sample size, and thus non powered to detect modest differences in the key outcome measures. In add-on there were 3 of import sources of dilution effects: firstly, just 63% of intervention grouping participants received some blazon of financial award; secondly, nosotros found that 14% of those in the trial eligible for financial benefits did non receive their coin until after the follow up assessments had been carried out; and thirdly, many had received their benefits for but a brusk menstruation, reducing the possibility of detecting whatever measurable effects at the fourth dimension of follow-up. All of these factors provide some caption for the lack of a measurable effect between intervention and command group and between those who did and did not receive additional financial resource.

The number of participants in the qualitative study who received additional financial resources as a result of this intervention was small (due north = 14). We would argue that the fieldwork, analysis and interpretation [46] were sufficiently transparent to warrant the caste of methodological rigour advocated by Barbour [7, 17] and that the findings were therefore an authentic reflection of what was being studied. However, there all the same remained the possibility that a reason for the discrepant findings was due to differences between the qualitative sub-sample and the parent sample, which led united states to step three.

(iii) Exploring dataset comparability

Nosotros compared the qualitative and quantitative samples on a number of social and economic factors (Tabular array 2). In comparing to the parent sample, the qualitative sub-sample was slightly older, had fewer men, a higher proportion with long-term limiting illness, but fewer current smokers. Still, there was nothing to indicate that such pocket-sized differences would account for the discrepancies. There were negligible differences in SF-36 (Physical and Mental) and HAD (Anxiety and Depression) scores between the groups at baseline, which led the states to discount the possibility that those in the quantitative sub sample were markedly different to the quantitative sample on these outcome measures.

(iv) Collection of additional data and making farther comparisons

The divergent findings led us to seek further funding to undertake collection of boosted quantitative and qualitative information at 24 months. The quantitative and qualitative follow-upwards information verified the initial findings of each study. [45] We besides nerveless a express amount of qualitative data on the perceived impact of resources, from all participants who had received additional resources. These data are presented in effigy 1 which shows the uses of additional resources at 24 calendar month follow-up for 35 participants (N = 35, 21 previously in quantitative study only, 14 in both). This dataset demonstrates that similar bug emerged for both qualitative and quantitative datasets: send, savings and 'peace of mind' emerged as key issues, but the information as well showed that the additional money was used on a broad range of items. This follow-up confirmed the initial findings of each written report and further, indicated that the perceived bear on of the additional resources was the same for a larger sample than the original qualitative sub-sample, further confirming our view that the positive findings extended beyond the fourteen participants in the qualitative sub-sample, to all those receiving additional resources.

Use of additional resources at 2 year follow up (N = 35)*.

(v) Exploring whether the intervention nether study worked equally expected

The qualitative study revealed that many participants had received welfare benefits via other services prior to this study, revealing the lack of a 'clean slate' with regard to the receipt of benefits, which nosotros had not anticipated. We investigated this further in the quantitative dataset and plant that 75 people (59.5%) had received benefits prior to the report; if the commencement do good was on health grounds, a after ane may have been considering their health had deteriorated further.

(vi) Exploring whether the outcomes of the quantitative and qualitative components match

'Probing certain problems in greater depth' as advocated past Bryman (p134) [1] focussed our attention on the effect measures used in the quantitative part of the written report and revealed several challenges. Firstly, the qualitative study revealed a number of dimensions not measured by the quantitative report, such equally, 'maintaining independence' which included affording paid aid, increasing and improving access to facilities and managing meliorate within the habitation. Secondly, some of the measures used with the intention of capturing dimensions of mental wellness did not adequately encapsulate participants' accounts of feeling 'less stressed' and 'less depressed' by financial worries. Probing both datasets also revealed congruence along the dimension of physical wellness. No differences were institute on the SF36 physical calibration and participants themselves did not expect an improvement in concrete health (for reasons of historic period and chronic health problems). The real issue would appear to be measuring means in which older people are better able to cope with existing health bug and maintain their independence and quality of life, despite these weather.

Qualitative study results also led u.s.a. to await more than carefully at the quantitative measures nosotros used. Some of the standardised measures were not wholly applicable to a population of older people. Mallinson [47] also found this with the SF36 when she demonstrated some of its limitations with this age group, too as how easy it is to, 'autumn into the trap of using questionnaires like a grade of laboratory equipment and forget that ... they are open to interpretation'. The information presented here demonstrate the difficulties of trying to capture complex phenomena quantitatively. Notwithstanding, they also demonstrate the usefulness of having alternative data forms on which to draw whether complementary (where they differ but together generate insights) or contradictory (where the findings conflict). [xxx] In this written report, the complementary and contradictory findings of the 2 datasets proved useful in making recommendations for the design of a definitive written report.

Discussion

Many researchers empathise the importance, indeed the necessity, of combining methods to investigate circuitous health and social issues. Although quantitative inquiry remains the dominant prototype in wellness services research, qualitative research has greater prominence than before and is no longer, as Barbour [42] points out regarded as the 'poor relation to quantitative enquiry that it has been in the past' (p1019). Brannen [48] argues that, despite epistemological differences in that location are 'more than overlaps than differences'. Despite this, there is continued debate nigh the potency of each private mode of research which is not surprising since these different styles, 'take institutional forms, in relation to cultures of and markets for knowledge' (p168). [49] Devers [50] points out that the authorisation of positivism, peculiarly within the RCT method, has had an overriding influence on the criteria used to assess research which has had the inevitable effect of viewing qualitative studies unfavourably. Nosotros advocate treating qualitative and quantitative datasets equally complementary rather than in competition for identifying the true version of events. This, we argue, leads to a position which exploits the strengths of each method and at the same time counters the limitations of each. The process of interpreting the meaning of these divergent findings has led united states of america to conclude that much can be learned from scientific realism [51]which has 'sought to position itself as a model of scientific explanation which avoids the traditional epistemological poles of positivism and relativism' (p64). This stance enables investigators to take account of the complexity inherent in social interventions and reinforces, at a theoretical level, the problems of attempting to measure the touch on of a social intervention via experimental means. Nevertheless, the current focus on evidence based health care [52] now includes public health [53, 54] and there is increased attention paid to the results of trials of public health interventions, attempting as they do, to capture circuitous social phenomena using standardised measurement tools. Nosotros would contend that at the very least, the inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative elements in such studies, is essential and ultimately more cost-constructive, increasing the likelihood of arriving at a more thoroughly researched and better understood set of results.

Determination

The findings of this study demonstrate how the use of mixed methods tin can pb to different and sometimes alien accounts. This, we argue, is largely due to the issue measures in the RCT not matching the outcomes emerging from the qualitative arm of the study. Instead of making assumptions most the correct version, we have reported the results of both datasets together rather than separately, and abet six steps to interrogate each dataset more fully. The methodological strategy advocated by this approach involves contemporaneous qualitative and quantitative information collection, analysis and reciprocal interrogation to inform interpretation in trials of complex interventions. This approach also indicates the need for a realistic appraisal of quantitative tools. More widespread utilize of mixed methods in trials of complex interventions is probable to enhance the overall quality of the evidence base.

References

-

Brannen J: Mixing Methods: qualitative and quantitative research. 1992, Aldershot, Ashgate

-

Tashakkori A, Teddlie C: Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioural Enquiry. 2003, London, Sage

-

Morgan DL: Triangulation and it'southward discontents: Developing pragmatism as an alternative justification for combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Cambridge, eleven-12 July.. 2005.

-

Pill R, Stott NCH: Concepts of illness causation and responsibility: some preliminary data from a sample of working class mothers. Social Science and Medicine. 1982, 16: 43-52. 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90422-1.

-

Scambler One thousand, Hopkins A: Generating a model of epileptic stigma: the role of qualitative assay. Social Science and Medicine. 1990, 30: 1187-1194. 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90258-T.

-

Townsend A, Hunt K, Wyke S: Managing multiple morbidity in mid-life: a qualitative study of attitudes to drug use. BMJ. 2003, 327: 837-841. 10.1136/bmj.327.7419.837.

-

Barbour RS: Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: the example of the tail wagging the dog?. British Medical Periodical. 2001, 322: 1115-1117.

-

Pope C, Mays N: Qualitative Research in Health Care. 2000, London, BMJ Books

-

Bryman A: Quantity and Quality in Social Research. 1995, London, Routledge

-

Ashton J: Salubrious cities. 1991, Milton Keynes, Open up University Press

-

Baum F: Researching Public Wellness: Backside the Qualitative-Quantitative Methodological Debate. Social Scientific discipline and Medicine. 1995, forty: 459-468. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)E0103-Y.

-

Donovan J, Mills N, Smith Thousand, Brindle L, Jacoby A, Peters T, Frankel S, Neal D, Hamdy F: Improving blueprint and conduct of randomised trials by embedding them in qualitative research: (ProtecT) study. British Medical Periodical. 2002, 325: 766-769.

-

Cox Grand: Assessing the quality of life of patients in phase I and II anti-cancer drug trials: interviews versus questionnaires. Social Scientific discipline and Medicine. 2003, 56: 921-934. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00100-4.

-

Lewin S: Mixing methods in circuitous health service randomised controlled trials: enquiry 'all-time practice'. Mixed Methods in Health Services Research Briefing 23rd Nov 2004, Sheffield University.

-

Cresswell JW: Mixed methods research and applications in intervention studies.: ; Cambridge, July 11-12. 2005.

-

Cresswell JW: Enquiry Design. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2003, London, Sage

-

Barbour RS: The case for combining qualitative and quanitative approaches in health services inquiry. Journal of Health Services Enquiry and Policy. 1999, iv: 39-43.

-

Gabriel Z, Bowling A: Quality of life from the perspectives of older people. Ageing & Order. 2004, 24: 675-691. 10.1017/S0144686X03001582.

-

Koops L, Lindley RL: Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke: consumer interest in blueprint of new randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002, 325: 415-418. 10.1136/bmj.325.7361.415.

-

O'Cathain A, Nicholl J, Murphy Eastward: Making the most of mixed methods. Mixed Methods in Health Services Enquiry Conference 23rd Nov 2004, Sheffield University.

-

Denzin NK: The Research Deed. 1978, New York, McGraw-Hill Book Company

-

Roberts H, Curtis K, Liabo K, Rowland D, DiGuiseppi C, Roberts I: Putting public health show into do: increasing the prevalance of working smoke alarms in disadvantaged inner city housing. Periodical of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2004, 58: 280-285. 10.1136/jech.2003.007948.

-

Rowland D, DiGuiseppi C, Roberts I, Curtis K, Roberts H, Ginnelly Fifty, Sculpher K, Wade A: Prevalence of working smoke alarms in local authority inner city housing: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Periodical. 2002, 325: 998-1001.

-

Vincent J: Old Historic period. 2003, London, Routledge

-

Department for Work and Pensions: Households beneath average income statistics 2000/01. 2002, London, Department for Work and Pensions

-

National Inspect Part: Tackling Pensioner Pverty: Encouraging accept-up of entitlements. 2002, London, National Inspect Role

-

Paris JAG, Player D: Citizens communication in general exercise. British Medical Journal. 1993, 306: 1518-1520.

-

Abbott S: Prescribing welfare benefits advice in primary care: is it a health intervention, and if so, what sort?. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2002, 24: 307-312. 10.1093/pubmed/24.4.307.

-

Harding R, Sherr L, Sherr A, Moorhead R, Singh S: Welfare rights advice in main intendance: prevalence, processes and specialist provision. Family Practice. 2003, 20: 48-53. ten.1093/fampra/20.one.48.

-

Morgan DL: Applied strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to wellness research. Qualitative Wellness Inquiry. 1998, viii: 362-376.

-

Moffatt Due south, White K, Stacy R, Downey D, Hudson E: The bear on of welfare advice in primary care: a qualitative report. Disquisitional Public Health. 2004, 14: 295-309. 10.1080/09581590400007959.

-

Thomson H, Hoskins R, Petticrew 1000, Ogilvie D, Craig N, Quinn T, Lindsey G: Evaluating the wellness effects of social interventions. British Medical Journal. 2004, 328: 282-285.

-

Department for the Environment TR: Measuring Multiple Deprivation at the Pocket-sized Area Level: The Indices of Deprivation. 2000, London, Department for the Envrionment, Trransport and the Regions

-

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36 item short form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992, 30: 473-481.

-

Snaith RP, Zigmond AS: The hospital feet and low calibration. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinivica. 1983, 67: 361-370.

-

Sarason I, Carroll C, Maton Thou: Assessing social support: the social back up questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983, 44: 127-139. 10.1037//0022-3514.44.1.127.

-

Ward R: The impact of subjective historic period and stigma on older persons. Journal of Gerontology. 1977, 32: 227-232.

-

Ford G, Ecob R, Hunt K, Macintyre S, West P: Patterns of class inequality in wellness through the lifespan: class gradients at fifteen, 35 and 55 years in the west of Scotland. Social Science and Medicine. 1994, 39: 1037-1050. ten.1016/0277-9536(94)90375-1.

-

SPSS.: v. 11.0 for Windows [program]. 2003, Chicago, Illinois.

-

STATA.: Statistical Software [plan]. viii.0 version. 2003, Texas, College Station

-

Ritchie J, Lewis J: Qualitative Research Exercise. A Guide for Social Scientists. 2003, London, Sage

-

Barbour RS: The Newfound Credibility of Qualitative Research? Tales of Technical Essentialism and Co-Pick. Qualitative Wellness Research. 2003, 13: 1019-1027. 10.1177/1049732303253331.

-

Silverman D: Doing qualitative research. 2000, London, Sage

-

Clayman SE, Maynard DW: Ethnomethodology and conversation analysis. Situated Order: Studies in the Social Organisation of Talk and Embodied Activities. Edited by: Have PT and Psathas G. 1994, Washington, D.C., Academy Press of America

-

White M, Moffatt Due south, Mackintosh J, Howel D, Sandell A, Chadwick T, Deverill M: Randomised controlled trial to evaluate the health effects of welfare rights advice in primary health intendance: a pilot report. Written report to the Department of Health, Policy Inquiry Program. 2005, Newcastle upon Tyne, Academy of Newcastle upon Tyne

-

Moffatt South: "All the divergence in the world". A qualitative report of the perceived impact of a welfare rights service provided in principal care. 2004, , Academy College London

-

Mallinson S: Listening to reposndents: a qualitative cess of the Short-Form 36 Health Status Questionnaire. Social Science and Medicine. 2002, 54: eleven-21. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00003-Ten.

-

Brannen J: Mixing Methods: The Entry of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches into the Research Process. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005, eight: 173-184. ten.1080/13645570500154642.

-

Green A, Preston J: Editorial: Speaking in Tongues- Multifariousness in Mixed Methods Enquiry. International Journal of Social Inquiry Methodology. 2005, 8: 167-171. 10.1080/13645570500154626.

-

Devers KJ: How will we know "adept" qualitative research when nosotros see it? Get-go the dialogue in Health Services Research. Health Services Research. 1999, 34: 1153-1188.

-

Pawson R, Tilley Northward: Realistic Evaluation. 2004, London, Sage

-

Miles A, Grayness JE, Polychronis A, Price N, Melchiorri C: Current thinking in the prove-based wellness care argue. Periodical of Evaluation in Clinical Practise. 2003, 9: 95-109. 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00438.x.

-

Pencheon D, Guest C, Melzer D, Grayness JAM: Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice. 2001, Oxford, Oxford University Press

-

Wanless D: Securing Good Health for the Whole Population. 2004, London, HMSO

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed hither:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/six/28/prepub

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank: Rosemary Bell, Jenny Dover and Nick Whitton from Newcastle upon Tyne City Council Welfare Rights Service; all the participants and general practice staff who took part; and for their extremely helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper, Adam Sandell, Graham Scambler, Rachel Baker, Carl May and John Bond. Nosotros are grateful to referees Alicia O'Cathain and Sally Wyke for their insightful comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional data

Competing interests

The writer(southward) declare that they take no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SM and MW had the original idea for the report, and with the assistance of DH, Adam Sandell and Nick Whitton developed the proposal and gained funding. JM nerveless the data for the quantitative study, SM designed and collected data for the qualitative study. JM, DH and MW analysed the quantitative data, SM analysed the qualitative data. All authors contributed to interpretation of both datasets. SM wrote the showtime draft of the paper, JM, MW and DH commented on subsequent drafts. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ii.0 ), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Moffatt, S., White, Thousand., Mackintosh, J. et al. Using quantitative and qualitative data in health services inquiry – what happens when mixed method findings conflict? [ISRCTN61522618]. BMC Health Serv Res 6, 28 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-half-dozen-28

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/1472-6963-6-28

Keywords

- Mixed Method

- Welfare Benefit

- Mixed Method Research

- Divergent Finding

- Financial Vulnerability

strasserpoine1948.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-6-28

0 Response to "The Only Measure of Center That Can Be Found for Both Quantitative and Qualitative Data Is the"

Post a Comment